Bacon as a weapon of mass destruction

by Arun Gupta

Illustrations by Jennifer

Lew and Ryan Dunsmuir

From the July 24, 2009, issue of The Indypendent.

Among my fondest childhood memories is savoring a strip of perfectly cooked bacon that had just been dragged through a puddle of maple syrup. It was an illicit pleasure; varnishing the fatty, salty, smoky bacon with sweet arboreal sap felt taboo. How could such simple ingredients produce such riotous flavors?

That was then. Today, you don’t need to tax yourself applying syrup to bacon — McDonald’s does it all for you with the McGriddle. It conveniently takes the filling for an Egg McMuffin, an egg, American cheese and pork product, and nestles it in a pancake-like biscuit suffused with genuine fake-maple syrup flavor.

The McGriddle is just one moment in an era of extreme food combinations — a moment in which bacon plays a starring role from high cuisine to low. There’s bacon ice cream; bacon-infused vodka; deep-fried bacon; chocolate-dipped bacon; bacon-wrapped hot dogs filled with cheese (which are fried and then battered and fried again); brioche bread pudding smothered in bacon sauce; there’s hard-boiled eggs coated in mayonnaise encased in bacon — called, appropriately, the “heart attack snack”; bacon salt; bacon doughnuts, cupcakes and cookies; bacon mints; “baconnaise,” which Jon Stewart described as “for people who want to get heart disease but [are] too lazy to actually make bacon”; Wendy’s “Baconnator,” six strips of bacon mounded atop a half-pound cheeseburger, which sold 25 million in its first eight weeks; and the outlandish bacon explosion, a barbecued meat brick composed of two pounds of bacon wrapped around two pounds of sausage.

It’s easy to dismiss this gonzo gastronomy as typical American excess best followed with a Lipitor chaser. Behind the proliferation of bacon offerings, however, is a confluence of government policy, factory farming, the boom in fast food and manipulation of consumer taste that has turned bacon into a weapon of mass destruction.

While bacon’s harmful effects were once limited to individual consumers, its production in vast porcine cities has become an environmental disaster. The system of industrialized hog (and beef and poultry) farming that has developed over the last 40 years turns out to be ideal for breeding novel strains of deadly pathogens such as the current pandemic of swine flu. If a new killer virus appears, like the Spanish Flu that killed tens of millions after World War I, factory farms will have played a central role in its genesis.

Concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) churn out cheap but flavorless meat. However, for the CAFOs to exist there must be demand for the product. That’s where the industrial food sector comes in. Chains like McDonald’s, Chili’s, Taco Bell, Applebee’s and Pizza Hut approach the tasteless, limp factory beef, pork and chicken as a blank canvas with which to create highly enticing, even addictive, foods by pumping it full of fat, salt, sugar, chemicals and flavorings.

The chains lard on bacon in particular as a high-profit method of adding an item that has a “high flavor profile,” a “one-of-a-kind product that has no taste substitute.” According to David Kessler, author of The End of Overeating, a standard joke in the restaurant chain industry goes, “When in doubt, throw cheese and bacon on it.” In essence, the chains conjure up endless variations on the McGriddle that itself is the mass-produced version of the maple syrup-soaked bacon strip from our childhood.

Thus, the crisis of factory farming becomes its own solution through the use of the industrially produced bacon. We know our industrial food system is killing the planet and killing us with heart disease, diabetes and cancer, but how can we resist when it tastes oh-so-good?

Our current food system has its roots in the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. With thousands of farming families fleeing the land, the Roosevelt administration dispensed credit and established price supports to stabilize the agricultural sector. The policy worked, but inadvertently created large grain surpluses. The problem of surpluses was temporarily alleviated by the demand created by the total mobilization of the state and nation during World War II. But after the war, the question of what to do with the excess production became more pressing.

The answer was to dump the surpluses, first on a devastated Europe, then during the Korean War and finally as “humanitarian aid” to Third World countries.

In the name of national food security, the U.S. government subsidized farmers to produce more food than Americans could eat, and to dump that surplus as a weapon in the Cold War. This policy favored economy of scale and technological innovation to increase yields, because managing overproduction was more effective if the farm sector was reduced and subsidies targeted at large-scale monoculture producers rather than farmers who produced a variety of goods or had small plots of land.

While the U.S. farm population had been shrinking since the late 18th century, when it was 90 percent of the general population, in 1940, on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II, some 18 percent of Americans were still farmers. By 1970 farmers accounted for only 4.6 percent of the populace because small farms could not compete with government-subsidized agribusiness.

It’s government policy that allowed CAFOs to come into being. Karl Polanyi argued decades ago in The Great Transformation that “laissez-faire was planned.” In other words, government regulation of land, labor and finance creates the conditions for free-market capitalism to operate.

The post-WWII period witnessed a series of agricultural revolutions that have been exported around the world, starting in the 1950s with the U.S.-led “Green Revolution” in cereal grains. In the 1970s, the “Livestock Revolution” went global. And the 1980s saw the “Blue Revolution” — factory farming of fish and seafood. Over the past few decades, global meat production has increased by more than 500 percent.

In Fast Food Nation, Eric Schlosser recounts the 1960s rise of Iowa Beef Packers (IBP), which revolutionized the beef industry. IBP came into being because it was able to exploit heavily subsidized water, fuel, land and grain for cattle feed; a national transportation infrastructure; and anti-union laws.

IBP’s innovation was to combine slaughterhouses with enormous cattle feedlots. In the slaughterhouses, IBP used Fordist production techniques to de-skill meat cutting, paid low wages and busted unions to drive prices down and rake in profits. Faced with relentless low-cost competition from IBP, other meatpackers had to adapt or die. By 1971, notes Schlosser, the last Chicago stockyard shut down. (The modern poultry industry, typified by Tyson Foods and Perdue Farms, got its start during World War II with the help of price controls and government-created demand.)

In the 1970s Smithfield Foods revolutionized hog production. According to a Rolling Stone 2006 expose', Smithfield “controls every stage of production, from the moment a hog is born until the day it passes through the slaughterhouse. [It] imposed a new kind of contract on farmers: The company would own the living hogs; the contractors would raise the pigs and be responsible for managing the hog shit and disposing of dead hogs. The system made it impossible for small hog farmers to survive — those who could not handle thousands and thousands of pigs were driven out of business.”

In the 1950s there were 2.1 million hog farmers in the United States with an average of 31 hogs each. As of 2007 there were just 79,000 hog farmers left, averaging over 1,000 hogs each. A single Smithfield subsidiary in Utah holds half-a-million hogs and produces more shit every day than all the residents of Manhattan.

Rolling Stone’s stunning report describes the lakes of manure that surround pig factories as Pepto Bismol colored because of the “interactions between the bacteria and blood and afterbirths and stillborn piglets and urine and excrement and chemicals and drugs.” (Vegetarians who think they are unaffected by this toxic fecal frappe should think again: The sludge is often used to “fertilize” crops that may find their way to your table.)

Beef, poultry and hog CAFOs could not exist without large-scale environmental devastation. Governments at every level exempt these operations from laws and regulations covering air pollution, water pollution and solid waste disposal. They are also largely free from proper bio-surveillance, that is, public monitoring to detect, track and report on the outbreak of diseases.

Mike Davis, author of The Monster at Our Door, writes that scrutiny of the interface between human and animal diseases is “primitive, often non-existent” because companies such as Smithfield, IBP and Tyson would have to spend money on surveillance and upgrade conditions at their hellish animal factories.

For Smithfield, devastating the environment is just a minor cost of doing business. In Virginia in 1997 the company was slapped with a $12.6 million fine for 6,982 violations of the Clean Water Act — an average of $1,800 per violation.

Rolling Stone paints a grim picture of what goes on inside a hog CAFO: “Sows are artificially inseminated and fed and delivered of their piglets in cages so small they cannot turn around. Forty fully grown 250-pound male hogs often occupy a pen the size of a tiny apartment. They trample each other to death. There is no sunlight, straw, fresh air or earth. The floors are slatted to allow excrement to fall into a catchment pit under the pens, but many things besides excrement can wind up in the pits: afterbirths, piglets accidentally crushed by their mothers, old batteries, broken bottles of insecticide, antibiotic syringes, stillborn pigs …”

Factory farms are a hotspot of new infectious diseases. According to a former chief of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Special Pathogens Branch, “Intensive agricultural methods often mean that a single, genetically homogeneous species is raised in a limited area, creating a perfect target for emerging diseases, which proliferate happily among a large number of like animals in close proximity.”

In his book Bird Flu, Michael Greger, MD, writes, “Factory farms are considered such breeding grounds for disease that much of the animals’ metabolic energy is spent just staying alive under such filthy, crowded, stressful conditions; normal physiological processes like growth are put on the back burner. Reduced growth rates in such hostile conditions cut into profits, but so would reducing the overcrowding. Antibiotics, then, became another crutch the industry can use to cut corners and cheat nature.”

But what happens when a poultry factory is doused with antivirals? According to Greger, “Say there’s a one in a billion chance of an influenza virus developing resistance to amantadine [an antiviral drug]. Odds are, any virus we would come in contact with would be sensitive to the drug. But each infected bird poops out more than a billion viruses every day. The rest of their viral colleagues may be killed by the amantadine, but that one resistant strain of virus will be selected to spread and burst forth from the chicken farm, leading to widespread viral resistance and emptying our arsenal against bird flu.”

To compound the problem, “the raising of swine is increasingly centralized in huge operations, often adjacent to poultry farms and migratory bird habits,” writes Mike Davis. These operations often abut cities, meaning the “superurbanization of the human population … has been paralleled by an equally dense urbanization of its meat supply.” These elements have produced an interspecies blender that is spitting out new viruses at an alarming rate, like the current swine flu bug.

While CAFOs excel in creating novel pathogens, they also churn out mountains of cheap but tasteless meat. So there is another important component to our deadly food system, and that’s the science and industrial manufacturing of highly processed foods.

Just as factory farms depended on government policies and regulations to exist, the processed food industry could not exist without industrial farming. In 1966 McDonald’s switched from using about 175 different suppliers of fresh potatoes to J.R. Simplot Company’s frozen French fry. Within a decade, notes Eric Schlosser, McDonald’s went from 725 outlets nationwide to more than 3,000.

Tyson did the same with chicken, which was seen as a healthy alternative to red meat. It teamed up with McDonald’s to launch the Chicken McNugget nationwide in 1983. Within one month McDonald’s became the number two chicken buyer in the country, behind KFC. The McNugget also transformed chicken processing. By 2000, Tyson made most of its money from processed chicken, selling its products to 90 of the 100 largest restaurant chains. As for the health benefits, Chicken McNuggets have twice as much fat per ounce as a McDonald’s hamburger.

The entire food industry, perhaps best described as “eatertainment,” has refined the science of taking the cheap commodities pumped out by agribusiness and processing them into foodstuffs that are downright addictive. Food is far more than mere fuel intake. Food is marketed as a salve for our emotional and psychological ills, and dining out as a social activity, a cultural outlet and entertainment.

To get us in the door (or to pick up their product at the supermarket), food companies stoke our gustatory senses. The food has to be visually appealing, have the right feel, texture and smell. And most of all, it has to taste good. To that end, writes Kessler in The End of Overeating, the food industry has homed in on the “three points of the compass” — fat, salt and sugar.

One anonymous food-industry executive told Kessler, “Higher sugar, fat and salt make you want to eat more.” The executive admitted food is designed to be “highly hedonic,” and that the food industry is “the manipulator of the consumers’ minds and desires.”

Referencing human and lab animal studies, Kessler shows how varying concentrations and combinations of fat and sugar intensify production of neurochemicals, much the same way cocaine does. One professor of psychiatry explains that people self-administer food in search of “different stimulating and sedating effects,” — much like a “speedball,” which combines cocaine and heroin.

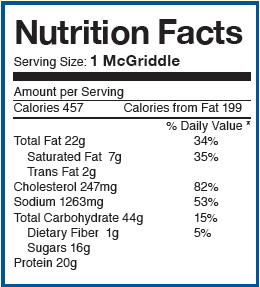

Kessler deconstructs numerous restaurant chain foods as nothing more than layers of fat, salt and sugar. Take the McGriddle: It starts with a “cake” of refined wheat flour (essentially a sugar), pumped with vegetable shortening, three kinds of sugar and salt. This cradles an egg, cheese and bacon topped by another cake. Thus, the McGriddle, from the bottom up, is fat, salt, sugar, fat and salt in the egg, then fat and salt in the cheese, fat and salt in the bacon, finished off with fat, salt and sugar. And this doesn’t indicate how highly processed the sandwich is. McDonald’s bacon, a presumably simple product, lists 18 separate ingredients, many of them used multiple times.

The success of the McGriddle and the Baconator has inspired an arms-race-like escalation among chain restaurants. Burger King’s French Toast Sandwich is nearly identical to the McGriddle. In 2004 Hardee’s went thermonuclear with its 1,420-calorie “Monster Thickburger,” laden with 107 grams of fat. And people are gobbling them up.

Perhaps you feel smug (and nauseated) by all this because you are a vegetarian, a vegan or a locavore, or you only eat organic and artisanal foods. Don’t. Americans are in the thrall of the food industry. More than half the population eats fast food at least once a week; 92 percent eat fast food every month; and “every month about 90 percent of American children between the ages of three and nine visit a McDonald’s,” states Schlosser.

The food industry has successfully appropriated the childhood creation of bacon dripping with syrup and repackaged it as a product that provides us with a coveted but deadly hit of salt, fat and sugar.

We know this food is killing us slowly with diseases like diabetes, heart disease and cancer. But we cannot stop, because we are addicts, and the food industry is the pusher. Even if we could opt out completely (which is almost impossible), it is still our land being ravaged, our water and air being poisoned, our dollars subsidizing the destruction, our public health at risk from bacterial and viral plagues.

Changing our perilous food system means making choices — not to shop for a greener planet, but to collectively dismantle factory farming, giant food corporations and the political system that allows them to exist. It’s a big order, but it’s the only option left on the menu.

home | music | democracy | earth | money | projects | about | contact

![]() Site design by

Matthew Fries | ©

2003-23 Consilience Productions. All Rights Reserved.

Site design by

Matthew Fries | ©

2003-23 Consilience Productions. All Rights Reserved.

Consilience Productions, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

All contributions are fully tax deductible.